The Axel Pinpin Propaganda Machine on country, freedom, and the people

By MC Galang

Collage by MC Galang; Stills courtesy of JL Burgos

“The revolution will be live.” – Gil Scott-Heron

I have to admit: I’ve only learned of Filipino protest band The Axel Pinpin Propaganda Machine when their video for “Ano Ang Aming Kasalanan?” circulated on Facebook last month. Helmed by filmmaker JL Burgos, the montage featured “triggering images of the government’s highly militarized handling of the COVID-19 pandemic juxtaposed with footage highlighting the brutality and violence that has swept the country under the current administration.”

As of June 25, there are 33,069 confirmed COVID-19 cases nationwide. Trade Union Congress of the Philippines (TUCP), the country’s biggest labor group, projects 12 million jobs will be lost by year-end—the highest unemployment rate in 15 years. According to the latest data from the ILOSTMYGIG.PH initiative, nearly 4,500 arts and culture workers have been affected, with the TUCP estimating 27 percent of the entire arts and recreation workforce finding themselves out of work.

Massive economic losses and spiraling healthcare conditions continue despite the 1.3 trillion peso stimulus package already approved by the House of Representatives earlier this month, with an additional record 4.3 trillion peso budget proposal for 2021, which aims to revive the pandemic-hit economy that was only recently experiencing a growth momentum. However, there is a gross lack of transparency from the government on spending of the initial stimulus budget, prompting a private citizen to head a tracker initiative that contains updates on allocations provided for each city or municipality.

In the midst of this, The Axel Pinpin Propaganda Machine puts a face on numbers, chipping away from the abstract notion of reality that often and easily reinforces desensitization and the dehumanization of the most vulnerable members of our society, one that the band has previously and consistently addressed in their work, such as “Recycle,” about using poor communities as scapegoats for disastrous waste and flood management, as if they themselves were nuisance and obstruction to progress; when it is in fact a result of imperialist plunder of natural resources, which according to environmental advocates, “hastens the destruction of the environment,” a case where “profit comes first; the environment and the people come second.”

“Ano Ang Aming Kasalanan?” was the protest band’s “response to the current health crisis which has exposed the harsh realities of repression, widespread social inequality, and the government’s incompetence – realities that have always existed and are now much more apparent.”

Formed in 2010 by RJ Mabilin of defunct punk band Republika de Lata and Axel Pinpin, poet and ex-political detainee wrongly imprisoned under the Arroyo regime, both activists have been independently releasing music “in response to the socio-political climate of the time,” including their first single “Remote Control” in 2011, which “chronicles the peasant and working class struggle in contrast to prevailing values of the bourgeoisie” and “Arman” in 2012, “which pays tribute to human rights defender Arman Albarillo, whose search for justice turned him into a martyred guerrilla fighter,” which was included in their debut album, Hindi Isasatelebisyon Ang Rebolusyon (2017), a direct translation of the 1971 spoken-word track by American jazz musician and poet Gil Scott-Heron, which today remains in the center of radical dissent in music. Scott-Heron notes in a 1990 interview:

The first change that takes place is in your mind. You have to change your mind before you change the way you live and the way you move. The thing that’s going to change people is something that nobody will ever be able to capture on film. It’s just something that you see and you’ll think, “Oh I’m on the wrong page,” or “I’m on I’m on the right page but the wrong note. And I’ve got to get in sync with everyone else to find out what’s happening in this country.

In a 2013 interview, Axel Pinpin spoke about art that “resonate[s] with cultural work as rooted in marginalized communities and cultural workers… how immersing themselves with the communities informs the creative aesthetic produced.” He said:

It developed in itself, within the National Democratic Movement, the term ‘cultural work’. It’s not very popular, you don’t hear that in the mainstream. What I want to say is unlike classical or what is called traditional Filipino culture, in terms of arts and culture, there is a culture within the national democratic orientation. Because of the kinds of marches, the kinds of poetry that ends with an exclamation point, the kinds of dances that moves in tempo with fists raised; maybe it’s become our stereotype, but it’s going to be appreciated.

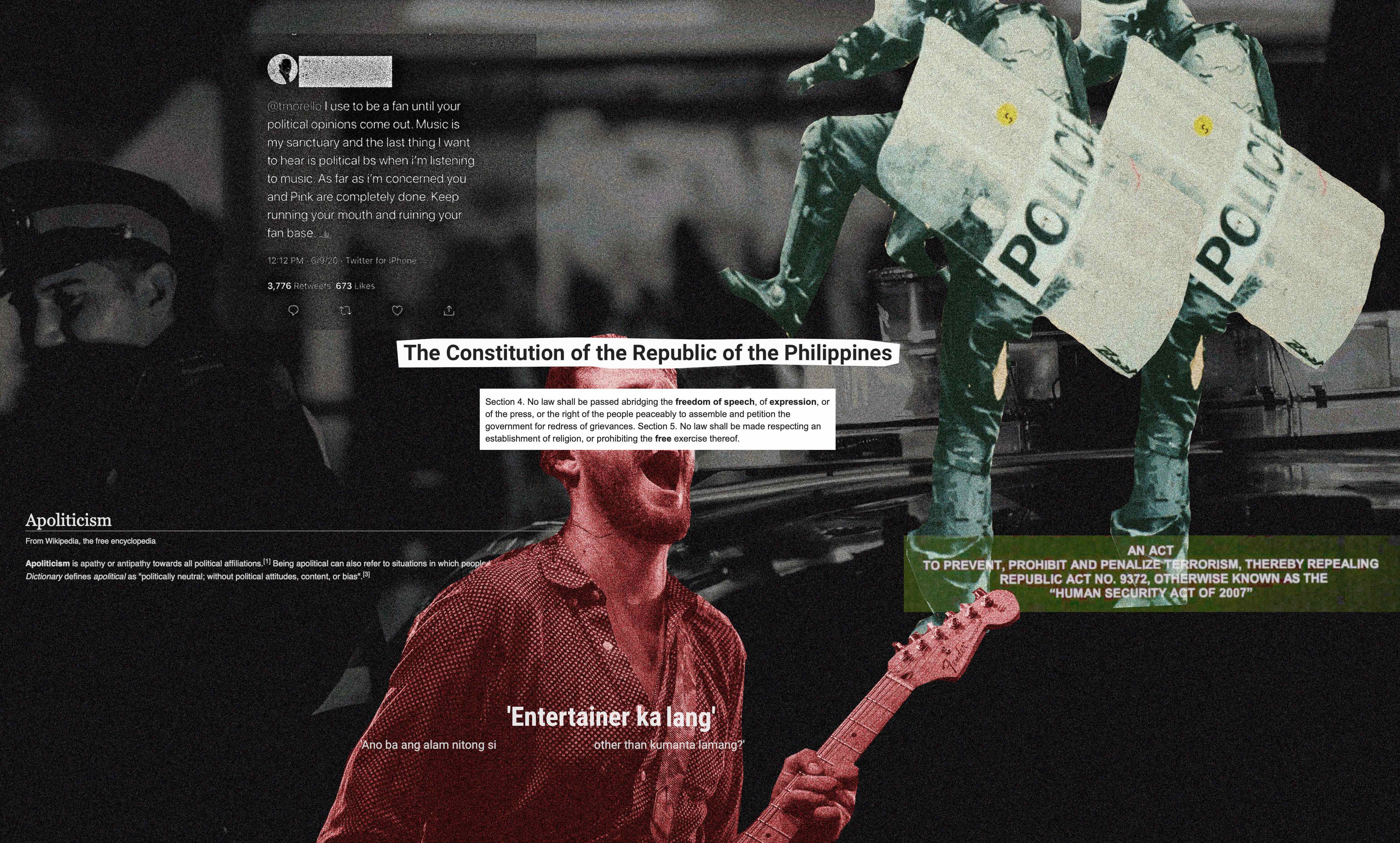

As the socio-political situation continues to devolve in the country, with the Anti-Terror Bill due to lapse into law in less than two weeks on what effectively counts as legislative sanctioning of force against our constitutional right to free expression, we reached out to The Axel Pinpin Propaganda Machine on their thoughts about where artists and citizens stand today and how can creative platforms be used to resist threats to our democracy.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Can you share with us who are the current, active personnel of The Axel Pinpin Propaganda Machine?

The Axel Pinpin Propaganda Machine’s (TAPPM) current lineup is composed of RJ Mabilin on guitars, Migs Gamara on bass, Megumi Acorda on guitars and keys, Jerros Dolino on drums, and Nigel Cristobal, who is in charge of audio and video playback. And of course, Axel Pinpin himself is still an active part of the band, albeit, not physically. Migs, Axel, and RJ are the remaining original members of the band.

Your album, Hindi Isasatelebisyon Ang Rebolusyon, was released in 2017, about a year into the Duterte administration. What were the most significant changes (and consistencies) did you observe regarding the socio-political situation and the public response then and now?

Firstly, we believe the economic, political, and even cultural relations that make up our current socio-political situation are still fundamentally the same as in previous administrations. The very basic demands of the people then – genuine land reform for the farmers, living wage, and job security for the workers, accessible if not free education, health and other social services, among others – remain the same. The government is still largely run by trapos who are (or are serving the interests of) landlords and big businesses, both local and foreign. This may all sound like cliché tibak lingo, but it couldn’t be truer especially during this pandemic.

Having said that, what has changed perhaps is the level of blatancy, crassness, and impunity of the current administration in doing its “business.” We’ve reached a point where those in power can be caught red-handed but still lie straight to your face and get away with murder. This regime has, in its disposal, a supermajority in congress: lackeys that form the majority of supreme court justices and well-fed generals – a level of power that previous administrations only dreamt of having.

More and more people are speaking up and are becoming critical of the government on their own volition. The blatancy, crassness, and impunity have their price after all.

Now, in terms of public response, we’ve observed how the current administration has exploited social media in shaping public opinion. The previous administration has utilized trolls as well, but this regime’s employment of troll armies is unmatched. On a positive note, however, we can also see that trolls are becoming less effective especially during the pandemic. More and more people are speaking up and are becoming critical of the government on their own volition. The blatancy, crassness, and impunity have their price after all.

You mentioned that in Axel Pinpin’s absence, you focused on producing your own documentaries to integrate to your music and performances. There’s been a general criticism in the way our realities have been captured, particularly when it comes to human suffering. How do you make sure that you’re able to properly serve your story and the people in it and steer away from self-centered voyeurism?

It is important to note that in our case, the musical performance and the videos are not separate art forms. As such, what probably separates us from “self-centered voyeurism” is the fact that the words in our music voice out the demands of the people we portray in our songs. Additionally, as artists, we consider ourselves not merely as observers, but as part of the people’s struggle. To borrow a quote from Bertolt Brecht, we believe in the principle that “art is not a mirror held up to reality, but a hammer with which to shape it.”

The arts and culture industry are among the hardest hit during this pandemic. What are your thoughts on the following: the government’s response—historically and at present—when it comes to supporting this industry; on using artistic platform and influence to respond to this government’s policies and priorities; and regarding silence of the members of the industry and what it means.

The government’s inability to provide an enduring structural framework on how to advance the condition and social welfare of cultural workers through the years has been indicative of the current and the past administrations’ valuation of arts and culture. This is even further evident in how the existing regime has responded to the COVID-19 crisis by electing to deploy stopgaps via financial aids for displaced artists while we haven’t heard of any sustainable long-term solution on how they’ll ensure the industry’s survival amidst the pandemic. As a result, the members of the arts community are left having to figure out solutions by themselves and experimenting on different means such as online gigs and fundraisers.

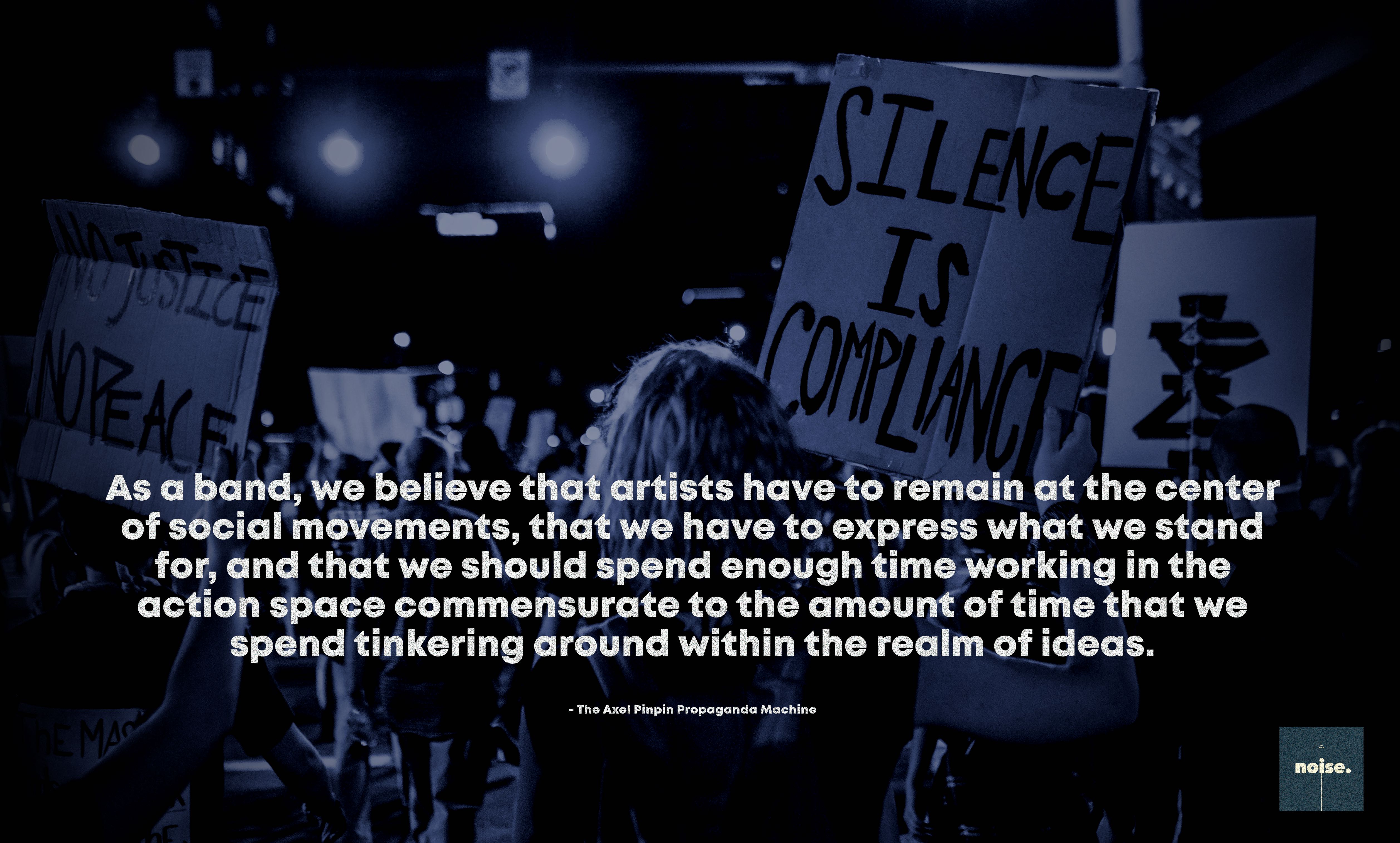

As a band, we believe that artists have to remain at the center of social movements, that we have to express what we stand for, and that we should spend enough time working in the action space commensurate to the amount of time that we spend tinkering around within the realm of ideas. As the crisis worsens, more and more artists and cultural workers within our circle are speaking up. We can expect that the number will exponentially increase as our collective voice becomes louder.

How did “Ano Ang Aming Kasalanan?”—the song and the video—come about?

“Ano Ang Aming Kasalanan?” was written about a year ago. It was originally intended to be a response to the rampant extrajudicial killings and illegal arrests of farmers and activists in Negros. The study for the music was written first, and Axel sent a draft of the poem which he recorded on his cellphone. We, however, became busy with other matters and the song was shelved.

Fast forward to last April, the worsening situation in our country due to the government’s ineptitude in handling the pandemic, combined with being stuck at home due to the quarantine, made it seem like there was no other choice but to create something new and relevant. We reviewed what material we had and realized that with a few slight adjustments, “Ano Ang Aming Kasalanan?” would perfectly fit the current situation. We recorded the instruments in our homes, sent files as well as ideas online back and forth.

As mentioned before, documentary-style videos are an integral part of our music, which meant that we knew from the very start that we wanted to produce one with someone we trusted. Filmmaker JL Burgos, brother of desaparecido activist Jonas Burgos, immediately came to mind since he just released a pandemic-related music video for another protest band, the Village Idiots. Fortunately, he was very willing to collaborate with the band. JL’s contribution to the song was definitely more than what we hoped for.

I want to ask: “legally,” this government is attempting to lawfully redefine what terrorism means. Artistic and rightful expression is under threat, and TAPMM has personally experienced this. What are your thoughts on this in general and the Anti-Terror Bill (ATB) specifically?

The discourse on what terrorism is or who the terrorists are in our country began during the rule of Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. It was a time when the threat of global terrorism took center stage, right after the 9/11 World Trade Center bombing in the United States. Around the same period in the Philippines, it was the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) who were perpetrating acts of terrorism such as bombings and kidnappings. Still, the Arroyo administration did not really consider them as primary threats. When the Bush administration included the Communist Party of the Philippines in its list of terrorist organizations, Arroyo followed suit.

The real target in these so-called wars against terrorism are the communists, and this still rings true. In a recent briefing, President Duterte categorically said the same thing: that they consider the communists (not groups like Abu Sayyaf) their number one threat. It is both laughable and alarming that amidst the pandemic, President Duterte consistently brings up the issue of communists and the NPA [National People’s Army].

Now, the danger here lies in the government’s red-tagging of almost everyone critical of them. With the ATB, they can now legally persecute anyone they have red-tagged. No matter how much the proponents of the law argue that activists are not the target, you have the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC), the police, the military, and rabid DDS (like Mocha Uson) who all have proven otherwise.

The political persecution of activists and government critics is not something new. Axel himself, along with four other activists, was arrested and detained for more than two years on false charges during Arroyo’s reign. Migs’s father is also currently illegally detained as a political prisoner.

We cannot let fear hold us back. We have to stop feeding the machine by being fearless, by struggling for our rights and our future.

To date, the arrests and killings of activists by the state remain rampant. Arming the government with this new ATB will only worsen the situation. As Senator Sotto himself said, we wouldn’t need Martial Law once the bill is passed.

What do you think “fear” means during these times?

Fear fuels the machinery of this current administration. It is the state’s primary enforcement tool that allows them to continue to assert its power, legitimacy, and authority over its people. It seeks to perpetuate its rule by weaponizing fear amongst us, thus the ATB, the fear-mongering through red-tagging, fabricating terror through fake news and its troll armies.

We cannot let fear hold us back. We have to stop feeding the machine by being fearless, by struggling for our rights and our future.

Stream Ano Ang Aming Kasalanan? on Spotify