Influenced heavily by the cultural and literary developments in Taiwan, Tsng-kha-lâng redefines indigenous consciousness with themes that mirror the esoteric life in rural Taiwan

By Ian Urrutia

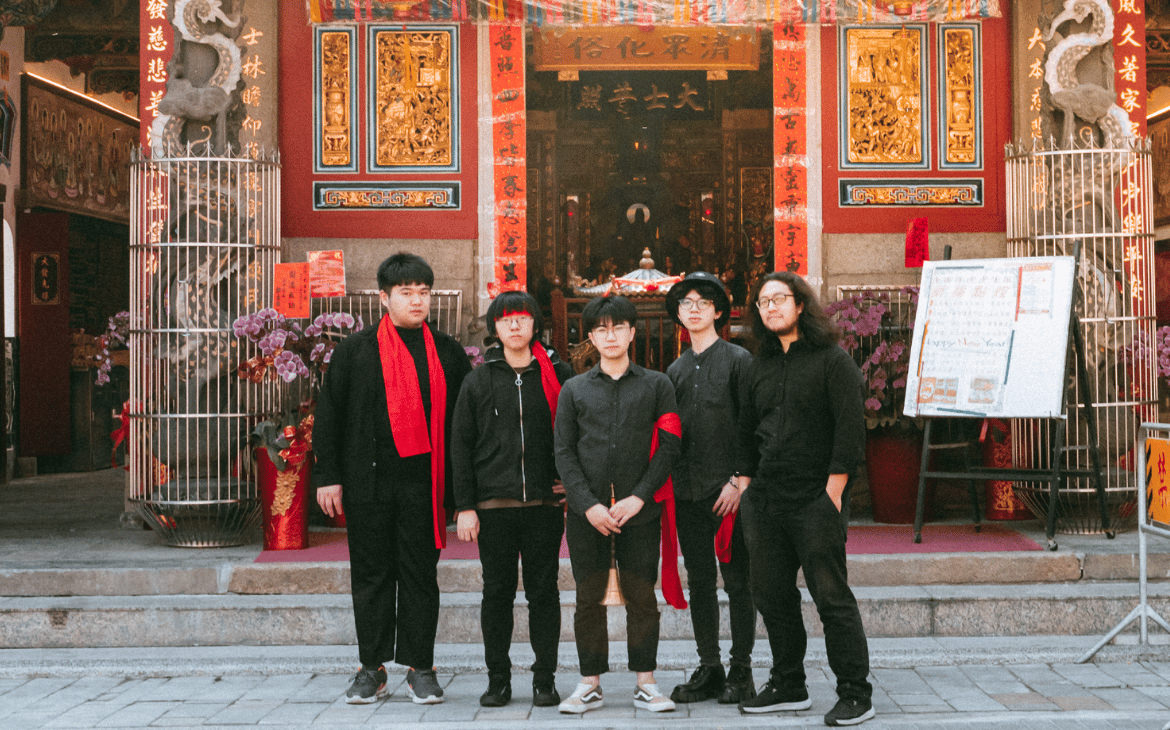

Tsng-kha-lâng has always been known for blazing a path forward with their compelling mix of psychedelic rock, folk, and traditional music. Outside of the conceptual façade that enthralled audiences across the globe, the five-piece act has secured their place in the pantheon of world music, thanks to their uncompromised understanding of Taiwanese history and the profound storytelling that serves as an integral part of their live performances.

Influenced heavily by the cultural and literary developments in Taiwan, Tsng-kha-lâng redefines indigenous consciousness with themes that mirror the esoteric life in rural Taiwan. The lyrics are often visual and poetic and filled with references to deities and spirits that try to find their way into the human realm.

For every captivating imagery that informs their music, it’s interesting how Tsng-kha-lâng connects the sublime with the historical developments in Taiwan as if it were part of reexamining the country’s ever-evolving cultural identity. As mentioned by the band themselves in the interview, their work embodies the sound of Taiwan: both the spiritual and the profound, the unspoken and the physical. But there lies their strong affinity with nature and the unsung heroes who suffered uncertain fates for political reasons. They honor these lonely souls through musical rituals that offer protection and blessings, and sometimes perform them with the dignified respect that they deserve.

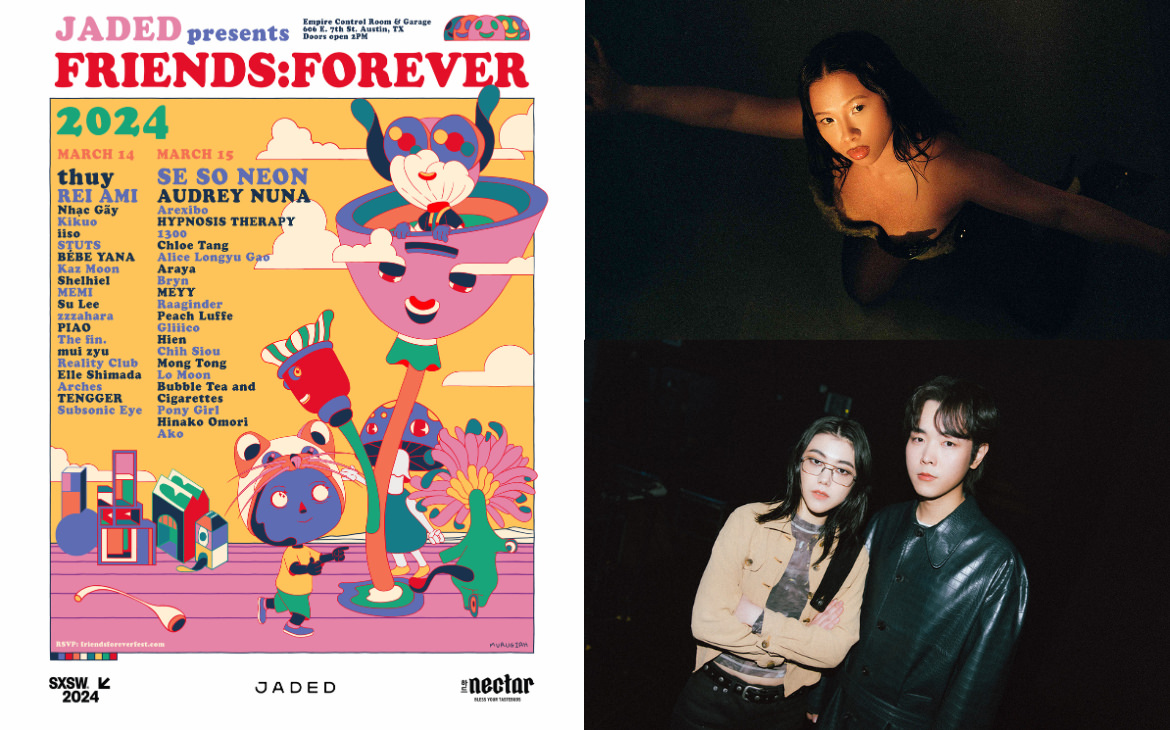

Prior to ahead of their showcase performance this week at 2023 World Music Festival @ Taiwan (WMF@Taiwan), The Rest Is Noise PH spoke to the band—composed of members Zhang Jiaxiang (vocals, xiaochao, tom-tom drums, suona), Dai Ruijun a.k.a. Dai Dai (vocals, copper bell, ringing lamp), Zhu Yumin a.k.a. Mills Chu (electric guitar, gong group), Zhang Shaowei (electric bass, toms), Li Yuanyan (jazz, northern and tong drums), and Huang Boyu (suona)—about how their music is closely rooted in historical and cultural studies related to Taiwan, their thoughts on cultivating their own musical identity, and the literary storytelling that inspired the creation and production of their debut album , Iā-Kuan Sûn-Tiûnn (夜官巡場).

How do Taiwanese history and religion inform your music?

Taiwan has experienced different periods of governance by various countries throughout its history. For instance, in the modern era, there was a transition of power from Japanese rule in 1945 to the rule of the Chinese Nationalist government. Many aspects of the cultural and literary developments of previous regimes are not widely recognized in contemporary Taiwan.

During the early years of the Chinese Nationalist government’s arrival in Taiwan, there were significant conflicts with the local population. Taiwan endured one of the longest periods of martial law in the world, lasting for a total of 38 years and 56 days.

During this time, many people who were imprisoned or died due to political reasons had uncertain fates. In Taiwanese folk beliefs, it is believed that when people pass away without anyone to perform rituals for them, their spirits become wandering and desolate, lingering in the human realm. Thus, against this backdrop, we use music to reexamine Taiwan’s history and each performance serves as a form of ritual to honor those lost souls who wander in the mortal world.

As a band that has significantly contributed to diversifying Taiwan’s traditional, indigenous, and world music for a global audience, what do you think sets you apart as far as identity and musicality is concerned?

Taiwan’s traditional music has been heavily influenced by various external cultures, with a profound impact from Chinese “Han culture.” For example, both Northern and Southern Chinese music, such as Beiguan and Nanguan, were originally introduced by Chinese immigrants. However, over the course of a long history, these musical traditions gradually became “localized” in Taiwan, giving rise to unique forms of Beiguan music with local characteristics. Building upon this cultural foundation, we have incorporated Western folk music and rock as the backbone of our music, along with these localized elements of traditional Taiwanese music and performance logic.

In the past, many rock bands and music creators in Taiwan would integrate traditional instruments like the suona and gongs and drums into their compositions. However, these integrations were not always based on a deep understanding of local culture. From the perspective of representing Taiwan’s distinctive musical identity, I believe that our music is one of the representative bands of this generation that best embodies the sound of Taiwan.

How do you describe your music? What are the elements that you incorporate to make your music uniquely and distinctly appealing?

Some people refer to us as Taiwan’s “funeral rock,” but we’re not that scary, actually. While we incorporate Taiwanese spirit-summoning rituals into our performances, a deeper understanding of the meaning behind these funeral rituals reveals that they all carry blessings and protection for both the deceased and the living. The underlying intention is warmth and kindness.

That being said, many members of our audience have given us feedback, saying that they feel an intangible presence watching over them during our performances. However, we’ve had a safe and peaceful journey in our performances thus far. If there’s anything uniquely attractive about our shows, it’s probably that both tangible life and intangible existence can be drawn to them (laughs).

Let’s talk about your lyrics. What are the topics or themes that you normally cover in your songwriting?

In our music, we often write about the rural lower-class people, spirits, and the deities left wandering unsupervised in the fields. These images are closely tied to the historical development of Taiwan. In fact, they represent the everyday life in rural Taiwan, and the face of life is related to historical developments.

For example, there is a song called “Tsuí-lâu-Má (Mother of the River).” She became a deity after being venerated as the River Goddess, and the temple of this deity is located in the rural village where I grew up. When I was a child, I found the temple of the River Goddess eerie and frightening. However, as I grew older, I realized that the temple’s history is closely linked to the local development.

Another example is our song ” Lîm Siù bī (Lin Xiumei).” She was the wife of Dr. Lu Yongqin, who was shot without trial by the Nationalist government’s army during the 228 Incident in Taiwan. She was a real figure from the era, living on the fringe of society and closely associated with spirits. After her husband’s death, society viewed her as something unusual and heretical, even though she had done nothing wrong. She had to bear this burden. So, we try to convey her feelings and perspective in our song, speaking to the emotions of “those who have survived” from her point of view.

Can you tell us more about your debut album, Iā-Kuan Sûn-Tiûnn (夜官巡場)? What is it all about? What inspired the entire process of production and creation?

When I was a child, in the bathroom of my home, I saw what looked like a wax-like statue of a jade maiden (in Taiwanese funerals, there are paper figures of young girls known as “jade maidens”). Her eyes were wide open, staring at me. She seemed unable to speak. When I grabbed my mother to come and see, the jade maiden had disappeared without a trace. Our home was in Fengshou Village in Minxiong, a place where the wind rustles through the rice fields like an ocean. Night officials, arhats, bodhisattvas, the River Goddess, or Lord Hou were all the gods I remember, the deities, wandering spirits, and the uncles and aunties I greeted every day. They were the truck drivers roaming around.

At that time, I often rode my bicycle, following the irrigation canals around the entire village. During the day, the village was under the management of the deities, but at night, it was the time for wandering spirits and lonely souls to patrol. It might have been frightening at times, but more often, these wandering spirits and lonely souls were simply a part of the village’s natural landscape. This album is a collection of songs I wrote for my hometown, for the burning village, for all the suffering lonely souls.

The album also inspired an upcoming novel penned by the Tiunn Ka-siông (張嘉祥). What can we expect from the novel? How did the music inspire its storytelling and content?

The text for Late Night Patrol of the Abandoned God (Iā-Kuan Sûn-Tiûnn) originated from the novel of the same name. It was written by the band leader, Jiaxiang, based on his childhood memories of the burning village in Minxiong, Chiayi, his hometown. Sometimes, the novel was transformed into songs, and at other times, the songs were created, with the novel extending from them. Jiaxiang considers the “Night Officials Patrolling” album and the novel as part of the same unified work. The music and the novel do not have a prequel or sequel relationship.

In the novel, the image of the night officials deity, featured on the cover of the Late Night Patrol of the Abandoned God album, is incorporated into the story. There has always been a legend in the burning village about the hidden treasure of the night officials, and those who receive the album are actually considered the ones who have found this hidden treasure and received the blessings of the night officials.

You’ll be performing at the World Music Festival @ Taiwan this year. How is it like representing the country at a prestigious global festival like this? What prompted you to say yes to the invitation?

We are very happy to participate in the World Music Festival@Taiwan. This is the second time our band has performed here. Each performance is an opportunity to meet with audiences and musicians from all around the world. Especially at the World Music Festival@Taiwan, we get to listen to performances by musicians from other parts of the world. We hear completely different sounds and contemplate their creative logic. It also prompts us to reflect on how we can improve our music. This is what makes us the happiest each time.

What are some of your most notable achievements as an artist so far? Any memorable festivals that you’ve played in recent memory?

Although we are a band focused on music creation and performance, our creative concept is closely intertwined with a novel text. The novel has received recognition in various circles in Taiwan. As a result, our performances often have a unique “storytelling” and “narrative” aspect that sets us apart from other bands. During our live shows, we frequently establish special and profound interactive relationships with the audience.

Additionally, our performance venues extend into the realm of literature, and we often collaborate with Taiwanese literary authors in cultural spaces dedicated to literature in Taiwan.

Regarding music festivals, we had the honor of participating in the “Megaport Festival,” which is currently the largest music festival in Taiwan. The bands featured in this festival are representative of Taiwan, which reflects the recognition our music and performances have received. During that performance, there was feedback from the audience. In the pitch-dark performance space, it seemed as if invisible individuals were listening to the music alongside them, shedding tears, and shouting. It left a deep impression.

Header and inline photos courtesy of the artist