Words by Aldus Santos

Illustration by MC Galang

When the OPM Archive Foundation was unveiled last August 26, I was cautiously optimistic. Name people put it up and money people are backing it, so it all sounded very, well, sound. In essence, the group aims to “collect Filipino music memorabilia and champion digital archiving,” which they say is a parallel but distinct effort from OPM-the-org’s. What this means is that items that are merely attendant to music-making—photographs, props, all manner of bric-a-brac—can have their time in the sun. This kind of thing gets me excited, because I care a great deal about the context surrounding creators and their creations: the backstories, the gear, the stuff previously discarded as refuse.

That it’s going to be crowdsourced sounds both promising and a total nightmare. But maybe I say that because while I’m big on cobbling stuff together, I habitually call for a snack break when it’s time to put things in some working order. Anyway, whether it’s tactile contributions (to be housed at the Filipinas Heritage Library) or digital ones (presumably to be housed here), this humble consumer of culture has some thoughts. Okay, they’re not entirely my thoughts; I talked to some friends who pay attention to this business, and I’m sharing some of those ideas here.

Situating music as sound

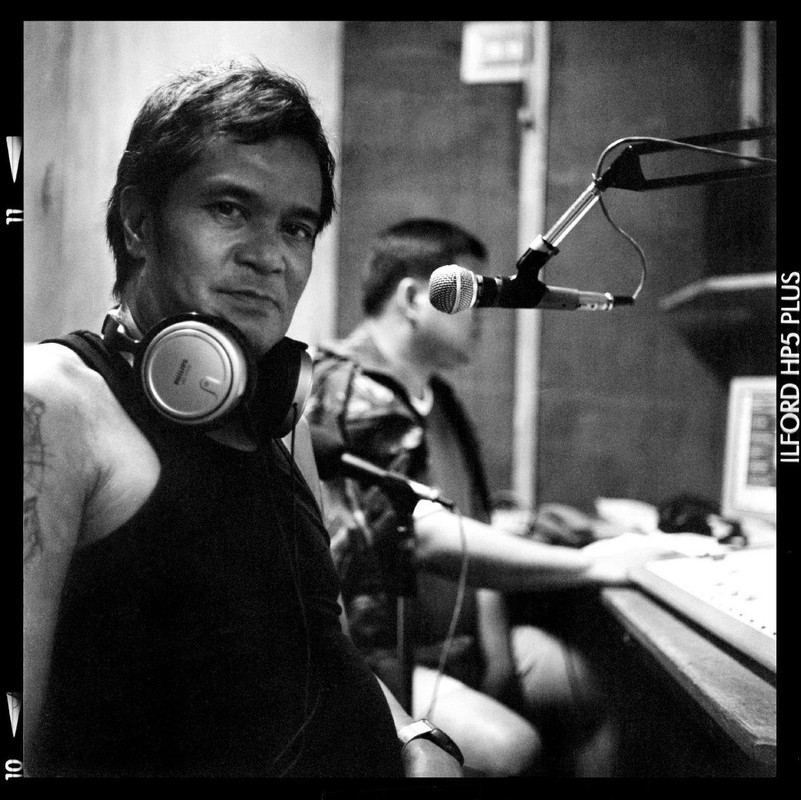

We consume music via different avenues now, but for a great long while, everyone only really ever had radio. A phone call with The Purplechickens bassist Mikey Abola, who used to DJ for the now-defunct RJ Underground Radio, yielded an idea for an interactive installation of DJ’s airchecks. It would situate the music in history, but also in aesthetics: 1970s AM or FM, obviously, would sound different from livestreamed on-boards. And come on, if you heard the late Howlin’ Dave intro some gnarly Pinoy punk, you wouldn’t have dared touch the dial.

Criticism as time portal

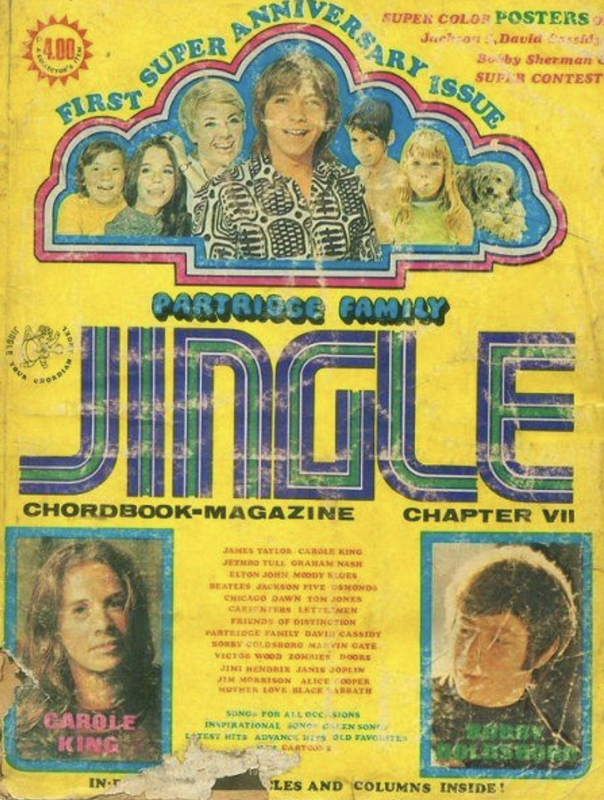

Edwin Sallan penned a cool feature on Gilbert Guillermo and Jingle a couple of weeks back, and it got me thinking: in lieu of present-day curation notes on past musicians, it would be interesting to track how music appreciation has, also, evolved through the years. Mr. Guillermo’s family would have kept, I’d imagine, most of the title’s celebrated run. Of course we shouldn’t stop at Jingle; even the copycat “songhits” in its wake had some gems. Imagine those things in microfilms (I’m old-school that way); it would both be gorgeous and educational.

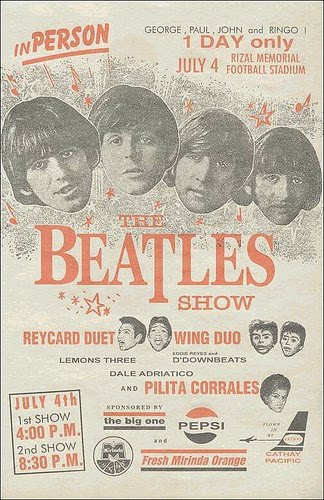

Poster art as art

Predictable entry, I know. But if anyone kept real-deal posters from legendary shows (New Moon in ‘77, Pinoy Woodstock in ‘90), or even flyers for fleeting club dates (from On Disco to Dredd to any Olongapo joint), it would be more than a walk down memory lane; it would be like school.

All or nothing at all

The always-spirited guitarist Diego Castillo didn’t mince words when we talked. He basically said that all recorded Filipino output should be accounted for. You take the good, the bad, and the ugly. Maybe the yield will reveal much of the latter, but that shouldn’t matter. “That’s the point of archiving, right?” he scream-typed. As for narratives, he’s a fellow champion of the Olongapo legend, and because the focus there (during the bases’ heyday) was on music as skilled labor, oral history would be our best bet. That would probably entail shooting a laborious docu-series, but hey, nothing worthwhile is ever easy.

Music is life, vinyl is lifer

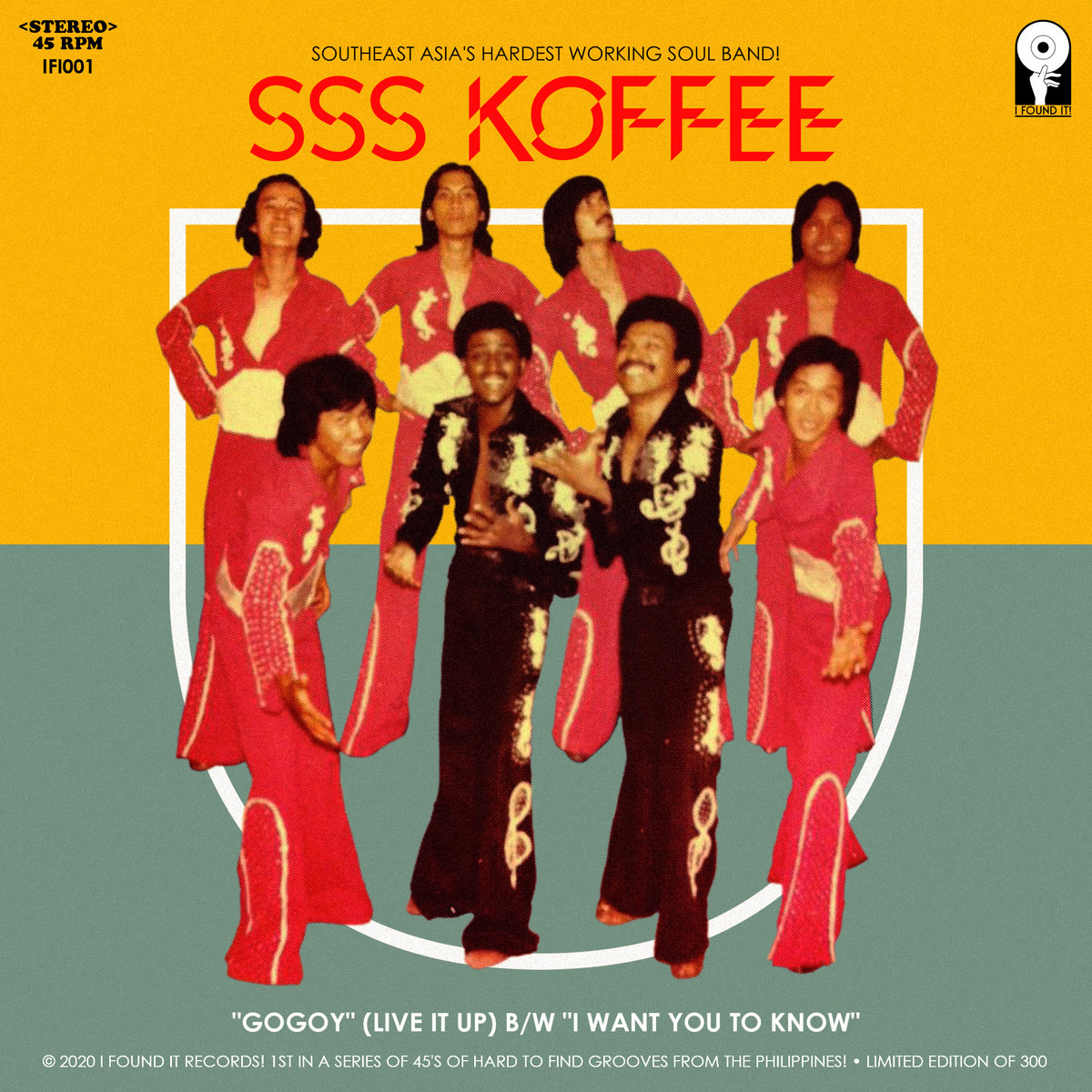

I also talked to the prodigious Diego Mapa, and between him and Castillo, vinyl is bound to come up. “All of it” is the intellectually honest route to take, but both Diegos agree that covering more obtuse titles would ultimately be more beneficial to us as a people and as a culture. A curation of the late Jose Maceda’s field recordings—a shared love between the namesakes—would be a great start, since as far as “original” Filipino music goes, those were literally it. As for leisurely listening, tracking titles from the Manila Sound era, as well as those cut by Pinoy jazzistas, is a no-brainer on any given day. I’m personally curious about the existence of a couple of pre-Dekada Ethnic Faces 7” singles, but that unhealthy obsession is for another discussion altogether. And even though the two Diegos continued to rattle off must-haves and already-haves like junkies—Dean’s December, some rare Anak Bayan, this really funky outfit called SSS Koffee, and the curious case of the D’Swan Records catalogue, which counted artists like The Lumberjacks, The Electromaniacs, and Eddie Peregrina and The Blinkers in its roster—Castillo still feels, “It [shouldn’t be] the Philippine Music Hall of Fame. It shouldn’t be subjective; it should be about archiving all the music that we have.”

Gear up

I believe in the talismanic qualities of gear, especially those that were used to make landmark recordings. This is perhaps my least concrete entry, but I don’t think it’ll hurt to have those genius-imbued instruments up on display: Mapa daydreams about having Bong Peñera’s piano or Francis Magalona’s samplers up there, as well as assorted bits of studio gear like vintage consoles and two-inch-tape machines. Me, I’m a simple-minded guitar guy, and I just want to see Nitoy Adriano’s battered Strat in there, or maybe Gary Granada’s cute round Yairi OK-1. I’m pretty sure you each have your own pick.

The realization Khavn and I arrived at, in so many words, is that if you’re unarchived, you’re uncredited.

Wrecked crew

If you ever saw The Wrecking Crew! (which I watched mostly for bassist Carol Kaye and drummer Hal Blaine), you’d imagine a similar merry band of mercenaries also existed here. The tragedy, however, is that session players are (almost always) never credited in old recordings, or if they were, the level of detail leaves much to be desired. (That’s kind of the labels’ fault, I think.) I talked to The Strangeness’ Francis Cabal about this, because I know his late parents were both working musicians (onstage and in-booth), and his staggering blindsidedness about the whole affair—as a child of unsung skilled laborers, but also as an independent musician whose imprint in local music is, similarly, rendered precarious by faulty historicizing—is frustrating. Can’t the guy pull a search for his folks from, like, a public-access database of studio logs and sessions? That would be the dream.

The revolution will not be archived

I talked to filmmaker-composer Khavn de la Cruz, too, and he lamented our disappointing history as archivists (or our disheartening record as recordists, LOL), which he feels should be rectified at all costs. “I mean, do you know who Jerry Brandy is?” he challenges the obscurantist in me. I put my arms up and say, “No, sorry.” To which he says, “Me, too! See?” before proceeding to explain how Brandy is supposedly a progenitor in the Yoyoy Villame school of novelty. The realization Khavn and I arrived at, in so many words, is that if you’re unarchived, you’re uncredited. (I mean you can be credited for shit, too, but your spot is yours and yours alone.)

Mababa kasi ang tingin [natin] sa music. Pampalipas-oras lang. Entertainment. Hindi kayamanan na dapat ingatan at alagaan.

Completist weirdoes are the future

An archiving idea is great, like, super-great. But I feel if any entity wants to get the ball rolling in any serious fashion, they can’t do their digging with a spoon. Others have come before them, and these people aren’t the usual suspects. There are researchers toiling in offices. There are collectors absentmindedly browsing through shelves. And then you have completist weirdoes like the late ex-banker Nestor Vera Cruz—proprietor of Yesteryear on Maginhawa-Magiting—whose fabled 20,000-title collection includes the very first record cut by any Filipino: an LP by the soprano sarswelista Maria Carpena.

I remember shooting a TV segment on Mang Nestor, and I’d point to a random album while my crew was dismantling gear. “Can I buy this?” I’d ask while holding up a record, and he’d go, “That’s not for sale.” I’d pick up another thing, ask to buy it, and again he’d go, “That’s not for sale.” And I recall being slightly pissed, thinking, “Did he just set up shop to brag?” But all jokes aside, succeeding reports would clarify that Yesteryear is more a free-access music library than a store (at the very least, only a small portion of the library is up for grabs). Khavn has actually adopted the digitization project started by the late collector, and while the Balangiga: Howling Wilderness director only has the nicest things to say about the man and his archive—which has reportedly since been acquired en masse by an equally rabid collector—he’s exasperated by our default stance on proper, responsible curation. “Mababa kasi ang tingin [natin] sa music. Pampalipas-oras lang. Entertainment. Hindi kayamanan na dapat ingatan at alagaan,” he hazards a guess.

If you’re unlike me and would rather not overthink things, donate to the OPM Archive here.