How my memories have both preserved and precluded my love for an artist’s growth

Words and Illustration by MC Galang

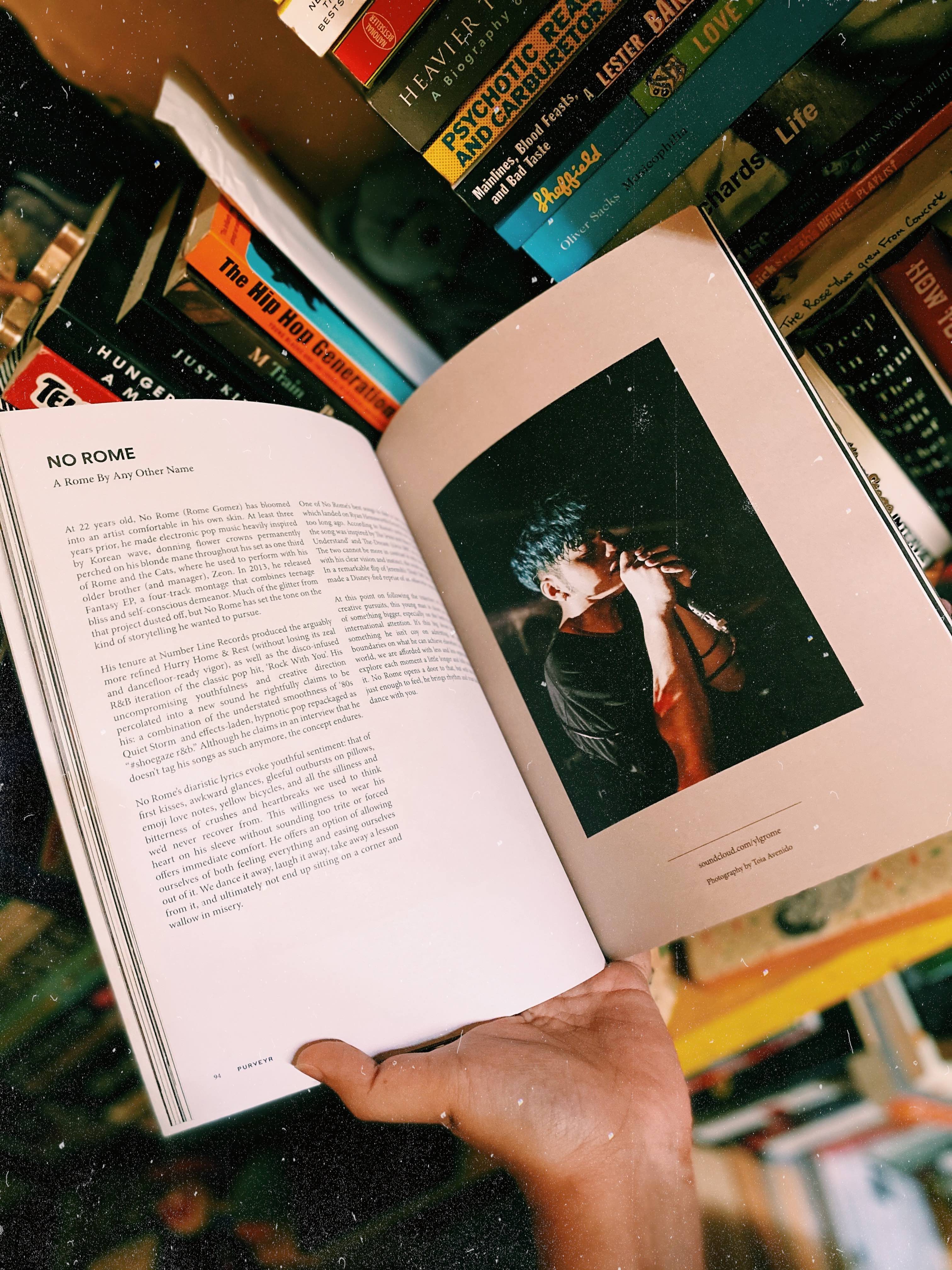

Artist image courtesy of No Rome

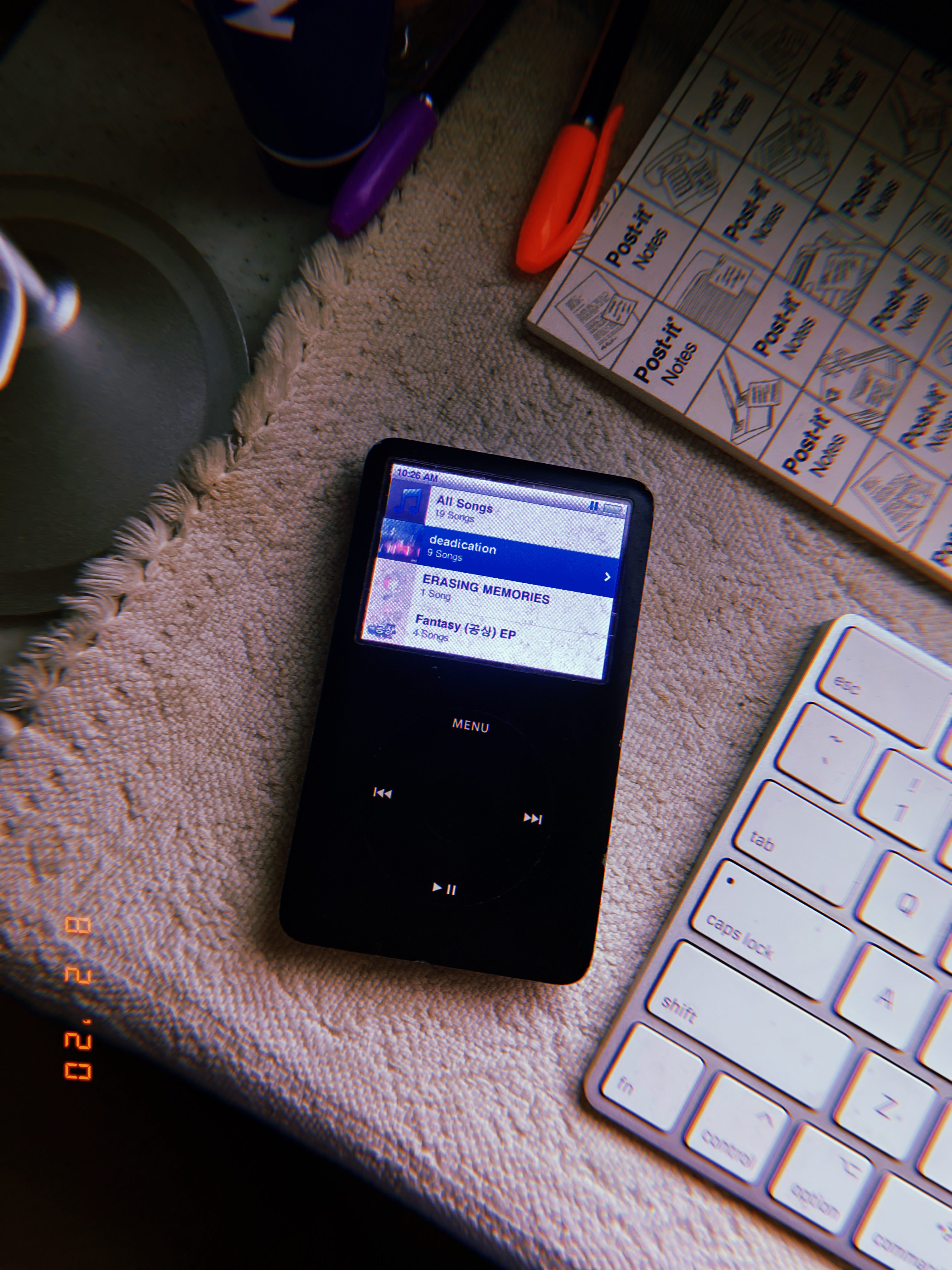

The first time I watched UK-based Filipino musician no rome was in Saguijo back in 2013 when he performed with Rome and the Cats, his then-band with Ethan Namoch (COEXIST, What is Andromeda) and his brother Zeon Gomez (ULZZANG PISTOL). They were giving away free copies of their artist collective Young Liquid Gang’s debut sampler (its first and last) that night, an eight-track mixtape also featuring Hana ACBD, Sczintillation, SOUL_BRK, and Spirit Ocean. I got myself one, immediately loaded the songs on my iPod, and eventually parted ways with the physical copy a few years ago.

I found myself going through no rome’s (née Rome Gomez) old catalog more as the singer-songwriter and producer continues to blaze trails abroad, working with Ryan Hemsworth’s Secret Songs label and eventually signing with UK-based Dirty Hit records, home of powerhouse artists like The 1975 and Rina Sawayama; performing at Coachella; and touring around the globe. In my mind, there’s a part that celebrates his success but there’s another, small but not quite insignificant region shrouded completely with nostalgia that somehow prevented me from listening—really listening—to his current work that resulted to crystallizing him in my own version.

Much of this has to do with how this particular period (early to mid-2010s) has fundamentally shaped my creative process as a writer and acquainting myself with the historical, cultural, and political nature of the music I consume on a regular basis. Being introduced to a whole spectrum of styles and genres, particularly electronica, and eventually identifying strongly with the queer communities it was originally and fundamentally made and advocated for became a potent tool that sculpted my own identity. But most of all, music has taught me complexities about the human condition.

Along with similarobjects, Nights of Rizal, June Marieezy, Tarsius, LUSTBASS, crwn, BP Valenzuela, Tandems’91, the disbanded Three.! and many others, no rome helped usher a beat-oriented and soul-infused sound into my consciousness that feels, for the first time, actually proximate and finally, physically accessible. As a result, I’ve written poorly written liturgies of some of the records these artists published on the now-defunct Vandals on the Wall. Of no rome’s Fantasy (2013), I wrote, “at first listen, [the EP] brings back nostalgic feelings of harmless firsts.”

His follow-up, the Number Line Records-released Hurry Home & Rest (2015)—one of his few remaining official and publicly available audio footprint online—relished in sparse, roomy textures demonstrating his maturity that’s “both welcome and unsurprising,” according to the liner notes. A year later, dedication (2016) arrived, a collection of vignettes that included a remix of tide/edit’s “Nicholas.” But perhaps my most favorite track so far was his Secret Songs’ release, “Ain’t Coming Back”—a soulful pop cut about the ownership of pain and the clarity of closures.

I last saw no rome perform live in Manila at our 16th show back in 2016, just before he jetted off to the U.K. I didn’t realize it at the time but it was also a sendoff to an entire chapter of my life.

Four years later, I revisited it.

no rome helped usher a beat-oriented and soul-infused sound into my consciousness that feels, for the first time, actually proximate and finally, physically accessible.

The latest track, “1:45 AM,” featured long-time collaborators bearface (BROCKHAMPTON), whom he worked with on 2016’s “No One Like U” and producer MJ Cole. Tender and vulnerable, it allowed me to access bygone days and memories, a remembering of the past through the present. The early-aughts UK garage production (most ostensibly reminiscent of Craig David’s 2000 debut Born to Do It) certainly helped facilitate this process. It took a recognizable sound in a flashy, extroverted time in pop music to reconstruct a lonely, mostly isolated time in my life. It may be sentimental and reactionary, as what often accompanies nostalgia, but listening to “1:45 AM” made me rethink how my eagerness to preserve my personal connection with no rome’s music stunted my ability to accommodate the progress he’s made as an artist.

The irony is that nostalgia was instrumental not only to my identity but also in developing tools on how to express myself. But in the process of acknowledging this personal breakthrough, I understood music critic Simon Reynolds’s question better: “Is nostalgia stopping our culture’s ability to surge forward, or are we nostalgic precisely because our culture has stopped moving forward and so we inevitably look back to more momentous and dynamic times?”

It may be sentimental and reactionary, as what often accompanies nostalgia, but listening to “1:45 AM” made me rethink how my eagerness to preserve my personal connection with no rome’s music stunted my ability to accommodate the progress he’s made as an artist.

On a more intimate level, it’s becoming increasingly hard these days not to ponder on the past, mostly because it is easier to compartmentalize our memories, which ones serve us comfort or conjure the warmth of happier times. But there are limits and there are dangers in lingering in it for too long. If there’s one more thing that no rome’s “1:45 AM” reminded me of, is that time governs and informs the way we negotiate with ourselves, our choices, the consequences of those choices, and what they mean.