Words by Ian Urrutia

Header and Layout by MC Galang

How artistic narratives in Filipino music shape LGBTQ+ consciousness—for better or worse

It’s a familiar scenario in a high school classroom during break time: the boys congregate at the back as soon as the teacher leaves for the next class. Obviously seeking for attention, they tap their armchairs and start singing along to their favorite Pinoy rock hits. Someone strums the guitar, while the other person seated next to him, asks for a new jam. Parokya Ni Edgar’s “This Guy Is In Love With You Pare” is queued next.

The happy bunch rallies behind it, a barkada anthem that delights in expressing a closeted friend’s romantic confession. Excitement fills the air—never mind if the singing sounds drunken and almost out of tune, or if the other group reviewing for an exam isn’t having it at all. The mere mention of “bading na bading sa’yo” elicits a chorus of macho-loud cheers, punctuated with a cathartic release. One of the guys point towards the direction of their only gay classmate. They turn their attention to this innocent person, calling him names. The group moves on to a different song. This time, it’s The Youth’s “Multong Bakla.” The room turns into a circus, but only the boys at the back are having fun. Seated in a quiet corner, the bullied guy puts on his headphones and tries his damn best to recover from the awkward situation. He blasts some music to accompany him in despair. It’s the only distraction available, his convenient escape from the harsh words that he receives almost every day. At least for that moment, he feels safe. He’s lucky that it only lasted for a few minutes.

Prejudice and stigma are propagated and reinforced by cultural agents.

It’s quite baffling how on few and rare instances that LGBTQ+ folks were included in the ‘OPM’ narrative, they’re either considered creeps that lure people into scam romance, slapstick sidekicks subjected to stereotypes, or predatory beings that deserve hate. The anecdote stated above rings familiar to every young teenage gay who thought being bullied based on sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression is just part of growing up, not knowing that it poses serious mental and social health problems in the long run. “Prejudice and stigma are propagated and reinforced by cultural agents,” says former National Youth Commissioner and Babaylanes, Inc. Educator Perci Villar Cendaña. “Music has the power to shape perception and consciousness.”

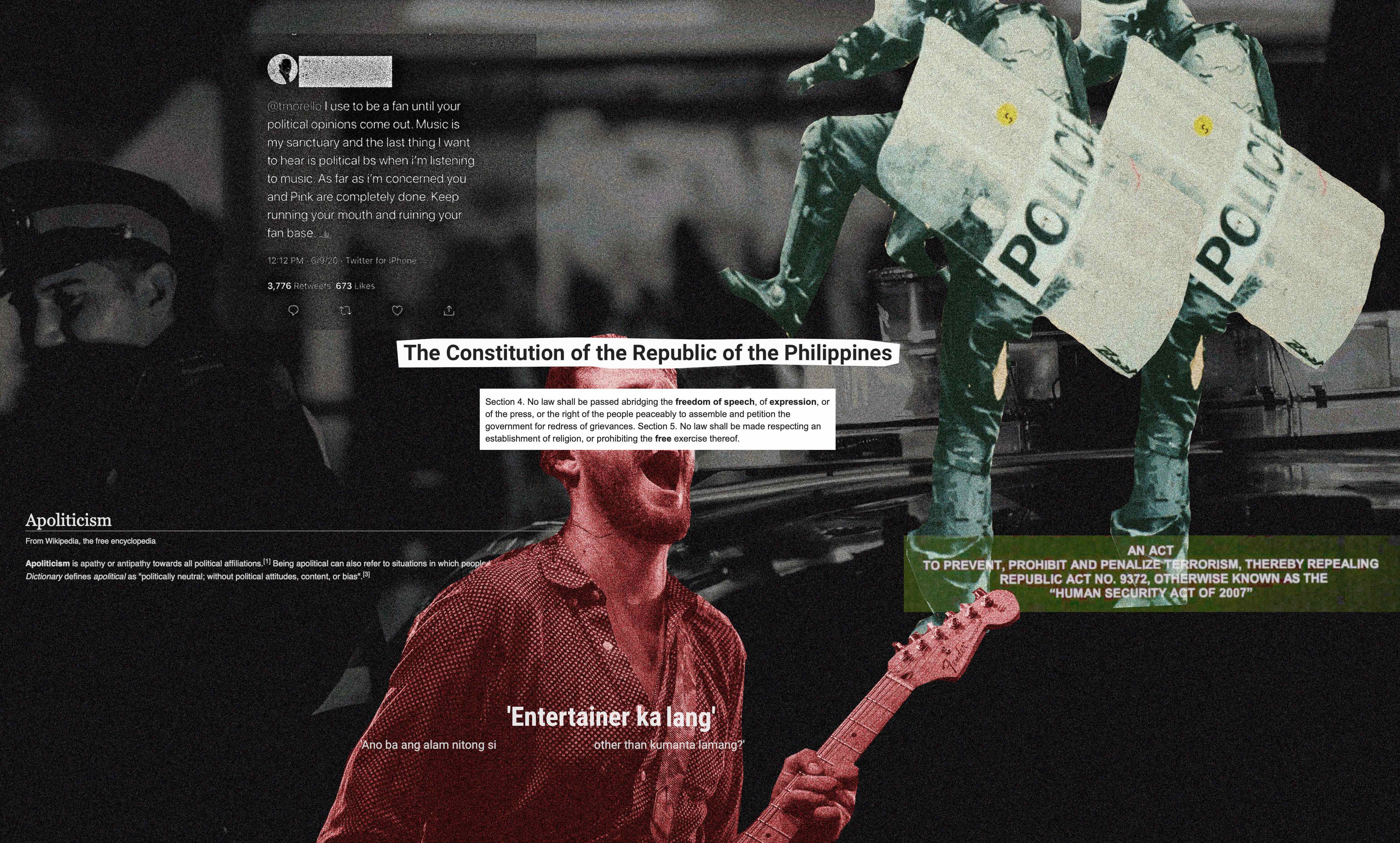

Some might argue that these songs were written to reflect the artist’s personal truths, and it is not, by any means, the creator’s duty to serve the greater good of mankind or pander to a specific movement or ideology other than his or her own. But one must be reminded of how songs, to quote singer-songwriter Vin Dancel, can sometimes “take a life of its own” outside of the songwriter’s point of view and intent. Once available for mass consumption, it becomes public property, and is not in any way exempted from scrutiny and critique. If created with no regard for sensitivity and tact, it can be used to reinforce violence and oppression against a marginalized group of people, most especially the LGBTQ+ community.

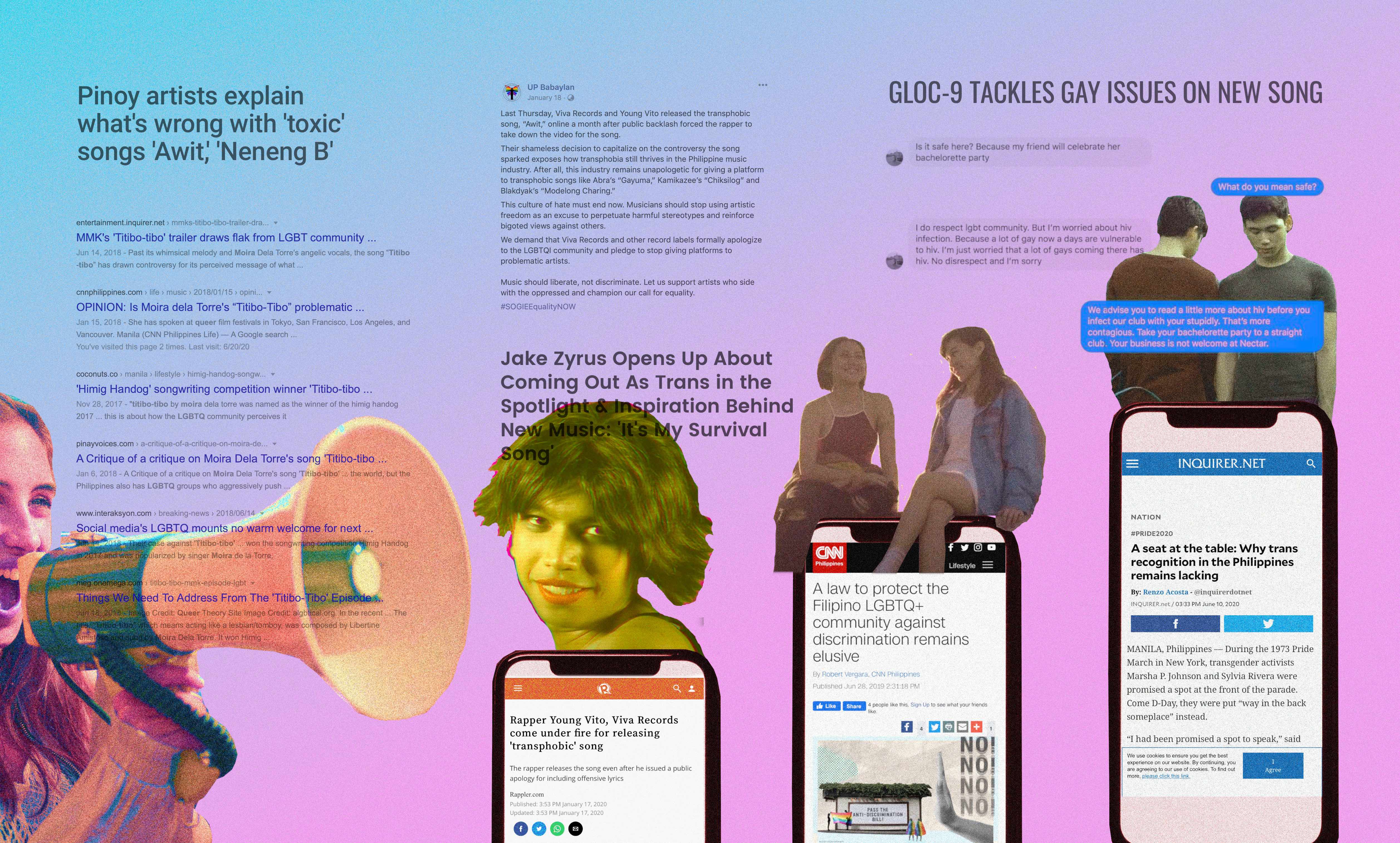

Trans shaming and violence

Songs like Blakdyak’s “Modelong Charing,” Kamikazee’s “Chiksilog,” Abra’s “Gayuma,” and Young Vito’s “Awit” have not only promoted a culture of homophobia and transphobia, but also relegated the subject of mockery into a scheming, one-dimensional character that does nothing but conceal their “biological attributes” to please the object of affection—in this case, the straight cisgender persona sharing primary or equal billing in the storyline.

From the problematic titles alone to the actual lyrics that propagate systemic othering of the transgender experience, these tracks hurl demeaning insults and offensive slurs that target those who refused to confirm to traditional gender roles assigned by the social order or the religious system. This kind of harmful depiction normalizes the established perception that transgender women are not women.

Haven’t we learned anything from Jennifer Laude’s murder? One Saturday night, she was found lifeless in a motel room in Olongapo City, her face rammed into a toilet bowl and her neck blackened with strangulation marks. According to reports, she died from “asphyxiation by drowning” and the man who did this to her, was only sentenced to a maximum of 12 years in prison. How about the workplace discrimination that University of the Philippines Assistant Professor Hermie Monterde had to endure? She admitted in her Facebook post about being on the receiving end of bullying from colleagues, with one of her co-professors insulting her by saying, “all males should dress up as males and all females should dress up as females.” What makes things even worse is her application for tenureship after teaching in UP for eight years, was denied on the basis of “interpersonal and professional concerns,” a proof of the academe’s institutionalized prejudice against trans women. And how can we not forget Gretchen Custodio Diez, who was prohibited from using a women’s restroom, verbally abused, and arrested after going live on Facebook?

From the problematic titles alone to the actual lyrics that propagate systemic othering of the transgender experience, these tracks hurl demeaning insults and offensive slurs that target those who refused to confirm to traditional gender roles assigned by the social order or the religious system.

“These songs, especially because of their popularity, have perpetuated and fueled the mainstream bias against transgender women,” Cendaña explains. “They do not only mock, they incite and justify violence and aggression because they cast transgender women in a very bad light.” Writer and pop culture critic Lakan Umali also shares Cendaña’s sentiments, adding that these songs don’t just propagate stereotypes: “They actively contribute to worsening transphobia by portraying discrimination against trans women as normal, even encouraged, because the songs portray trans women as ‘fooling’ men, therefore deserving of discrimination.”

Problematic depictions of lesbians

Even lesbians aren’t exempted from stereotyping and misrepresentation in scarce “opportunities” that they’re featured in Filipino songs. Three years ago, Moira Dela Torre’s “Titibo-tibo” caught flak for its problematic assertion that being lesbian is just a phase that can be corrected or cured. Despite the mixed reception, the ukulele-driven ditty won the top prize of a popular songwriting competition, which propelled it to the top of the streaming and radio charts in the Philippines.

Filmmaker and LGBTQ+ advocate Cha Roque finds the song troubling, as there are “still a lot of cases of corrective rape being done to tomboys and/or lesbians, where their family member asks someone to rape them believing that this will make them straight.” According to Roque, “It gives the wrong impression that being a lesbian or queer can be corrected. I’ve read that it was based on the songwriter’s own experience and I don’t want to invalidate that. But for someone with a huge following and a platform for sharing her songs, she needs to be more responsible on the way she represents tomboys in her songs.”

Acclaimed visual artist and writer Christian Tablazon acknowledges the “little promise there is toward the early parts of Moira’s ‘Titibo-tibo’ that potentially explores a girl’s relatively unconventional gender expression and performance,” but criticizes the song for its “crass rendition of the romantic makeover trope that merely fetishizes the tomboy and makes it a foil and takeoff point for the persona’s ‘true’ sexual awakening and subsequent transformation.” He adds, “True to most romance texts, her encounter with the ‘right man’ rouses the ‘woman’ in her, extinguishing prior deviant tendencies, and ultimately, she is reinscribed back to the heteronormative order.”

On rare occasions that a lesbian is depicted in a visual medium for music, she’s portrayed as a scorned, insecure villain who murders her partner for committing adultery. How groundbreaking.

Unfortunately, this isn’t the only instance that local music has shown numerous other harmful lesbian tropes. The music video of Soil And Green’s “Hello Sunrise” trivializes the possibility of having a more introspective and complex portrayal of lesbian relationships. Instead of helming a narrative that breaks new territory or contributes to the society’s understanding of the often ostracized segment of the population, the visual storytelling reinforces dangerous stereotyping of lesbian couples in media and film, where relationship entered by concerned parties is doomed because lesbians are not capable of maintaining serious commitment and monogamy—again, a hasty generalization seen in a lot of pop culture plots. On rare occasions that a lesbian is depicted in a visual medium for music, she’s portrayed as a scorned, insecure villain who murders her partner for committing adultery. How groundbreaking.

“On the music video, I don’t know their intention for the storyline but I felt like the lesbian plot was only used to draw attention,” Cha Roque shares this sentiment about the “Hello Sunrise” video. The LGBTQ+ filmmaker and activist didn’t mince her words on her frustrations about the tone-deaf and flat characterization of its two main leads. “I have attended several LGBT seminars where most people’s impression of lesbians is possessive, selosa, and the video did not veer away from that. I think it’s about time to see a different narrative on LGBTs. We do a lot of things, aside from just having sex and focusing on relationships. At one point it’s good to show our struggles in music videos and films, but I hope more will also delve into creating content that showcases our triumphs as well.”

Cendaña, on the other hand, emphasizes the need for artists and creatives to be conscious and sensitive of the plights and struggles of our LGBTQ+ comrades. He believes that while the folks behind Soil and Green’s music video never meant to disrespect or misrepresent the LGBT community, “the lack of understanding, grounding and appreciation of stigma, prejudice, and misogyny has resulted in materials that are discriminatory even if the creators meant well.”

Promising developments

The last two decades have somehow warmed up to engaging conversations about empowering queer visibility and imagery in local mainstream music, from anointing explicitly gay comedian Vice Ganda as one of TV, film, and music’s biggest superstars to the highly publicized transition of Jake Zyrus, which earned him a book and recording deal after. But perhaps, nothing is more controversial than the release of Gloc-9 and Ebe Dancel’s “Sirena,”—an inspiring anthem that addressed the violence and discrimination perpetuated against LGBTQ+. The song also brought to light the resilience of the gay character and how, to quote Everything Is Queer blog, he managed to “rise above oppressive situations and become empowered” himself. The song isn’t perfect, to say the least, especially on the contentious choice of inhabiting a first-person narrative without having experienced the systemic abuse and harassment that every LGBTQ+ person is forced to endure in real life. Christian Tablazon thinks it’s “patronizing and messianically inspirationalist.” Moreover, “The lyrics and music video are also ridden with clichés and stereotypes, flat characters, and melodramatic and slapstick stylizations, but perhaps the most unfortunate aspect of the project is how Gloc 9’s and Dancel’s first-person vocals deliberately seek to inhabit and ventriloquize queer subjectivity and struggle.”

Lakan Umali has a more positive take on “Sirena,” calling it “an important song which gives a well-crafted portrayal of growing up gay in the Philippines.” He says, “It’s a song which concretizes the experiences of many queer Filipinos, and makes them more understandable for a straight audience. It started an important conversation.”

Perci Villar Cendaña welcomes the song’s subversive intent and message and maintains, “It had and still has the power to call attention to the issue of violence and aggression against people of diverse SOGIE. I’ll leave it at that.”

Cha Roque didn’t feel offended at all about the song upon hearing it for the very first time. And despite its stereotypical representation, she commends the song for ending up in an empowering tone, where the video shows successful LGBTQ+ people from various sectors of society. “The story from the song is something we are all familiar with – from movies that laugh at gay people, our gay neighbor who gets beaten up by his dad. But then you hear this song and you are reminded that those forms of homosexuality we have always been exposed to are not okay.”

I think the real challenge is having more firsthand queer and trans expressions, having queer artists themselves represent and articulate queer identities and experiences, and having more representations with far more depth and complexity in the mainstream.

While we’re still far from educating the general public on sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression (SOGIE) and their importance in mobilizing social change, there is hope within the fringes of independent and underground music movements where LGBTQ+ folks are not only properly represented, but their ability to express themselves freely and independently, outside of mainstream society’s embrace of outdated patriarchal ideas and blatant consumerism, have given us little underrated tunes that explore the complexity of our experiences—be it the sexual or liberating kind, or plainly a celebration of coming out, or an admission of our collective fears in a country that invalidates our struggles and rights.

From BP Valenzuela’s brash portrayal of young gay romance on “bbgirl” and “Cards” to Ja Quintana’s inspiring lyrics on “Bahaghari”—to name a few, the queering of the musical niche has opened its doors for the LGBTQ+ community to reflect on its own history and confront the present with a more empowered but diverse storytelling modes and expressions. To borrow Lakan Umali’s words, “It’s expected that the indie music scene sees better LGBT visibility, since it’s not as constrained by market forces as the mainstream industry, and can deal with topics that more famous artists will shy away from.”

Christian Tablazon remains optimistic about queer representation in the local independent and experimental music scenes, but also hopes for a deeper and more nuanced exploration of LGBTQ+ narratives in cultural texts. “I think the real challenge is having more firsthand queer and trans expressions, having queer artists themselves represent and articulate queer identities and experiences, and having more representations with far more depth and complexity in the mainstream. I also hope that while distinct queer and trans experiences are articulated and celebrated on one hand, the ‘queer’ in OPM on the other hand need not be almost always marked by difference or alterity, and eventually thrive as normative. Either way, the queer in OPM should be allowed the numerous and various productive and dynamic possibilities for being sung and sounded.”

Awareness and Sensitivity

There is a need to raise awareness about the various problematic depictions of our LGBTQ+ comrades in cultural texts like music and film. It’s necessary to elevate the discourse and encourage progress in representation, because as agents of and for meaningful change, music has the power to uphold the legacy of those who fought for our liberation and rights, and drastically alter how people perceive the community.

The queer in OPM should be allowed the numerous and various productive and dynamic possibilities for being sung and sounded.

Roque stresses the importance of educating the artists and making them or the record label “accountable for homophobic content.” She shares, “If content has been released, be open for a discussion. Talk and discuss why a certain song is offensive to make the artists realize all the rage as well. Be open to discourse instead of just expressing your anger and shutting people off. It can be tiring but a lot of hate and ridicule really comes from ignorance.”

Tablazon takes the discussion seriously, and hopes for a more encouraging dialogue about LGBTQ+ representation in local music. “As educators, artists and cultural producers on the receiving end of problematic media, we could use our various platforms to attentively point out, call out, foster critical awareness, demand accountability, ensure that depictions do not betray their full and complex humanity, and encourage more ethical ways of apprehending and generating ‘queerness’ in our music and other media.”